- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- 'Bring Your Own' Deployment Models

-

- Products

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- NDR

- Analyze network events to detect and respond to advanced threats.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

-

- Industries

- Financial Services

- Healthcare

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Research

By Oliver Rochford, Security Evangelist, Securonix and Augusto Barros, Cybersecurity Evangelist, Securonix

While threat hunting is not entirely new [1], interest in the discipline has grown in recent years, mainly prompted by a growing number of attacks that bypass traditional detection technologies.

SANS has a growing library of content on the topic, and there’s even a NIST control. Searching on Google in January 2022 yields almost one and a half million hits:

There are a lot of people talking about it. The bigger question though is, are people actually doing this? And if so, why?

What Is Threat Hunting?

SANS formally defines threat hunting as:

“the formal practice of threat hunting [which] seeks to uncover the presence of attacker tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) within an environment not already discovered by existing detection technologies.”

To paraphrase, threat hunting is based on the assumption that we have been compromised, but our existing detection capabilities have not detected anything.

True threat hunting is proactive and preemptive. Members of the security team go out and actively search for the indirect signs or artifacts of an ongoing compromise, rather than waiting for something to happen or be detected. We assume have already been breached, but that our adversary is actively engaged in evading discovery and detection.

Threat hunting is not a technology. Threat hunting is a process typically conducted by a human analyst, although the hunter can be and is commonly augmented and the hunt semi-automated using a diverse toolbox of technologies.

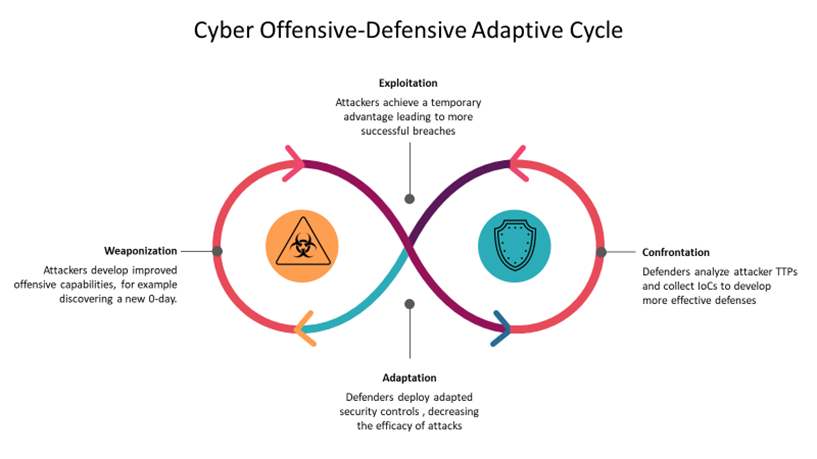

Threat hunting is one of the defensive adaptations in the cyber offense-defense adaptation cycle. It fills the gap between attacks being known and being programmatically formalized via detection code.

Why Threat Hunt?

Now that we’ve established what threat hunting is, let’s talk about why you’d do it. Why bother with a labor and effort-intensive process such as threat hunting? Shouldn’t detection alone be enough?

Many detection technologies can provide effective coverage if the specifics of a threat are known in advance, often called “known-knowns”, for example, the IP addresses and domain names used in the infrastructure to command and control the malware. But attackers routinely change these to evade easy detection. Even using a more dynamic way to keep signatures up to date, like machine-readable threat intelligence feeds, only reduces the time window that they are ahead and we can’t detect them, but it doesn’t eliminate it. Most detection technologies such as IDPS and WAF also require fresh attack traffic for detection – which leaves a blind gap if the technical details of an attack only become public knowledge after initial exploitation occurred.

Traditional detection technologies are especially challenged when indicators of compromise are not publicly available, for example, when:

- The threat has been active for a while before being discovered and/or publicly disclosed. Sunburst would be a recent example that falls under this category.

- The threat is highly evasive, for example with attackers living off the land by misusing legitimate applications or credentials, or by attacking supply chain trust relationships such as digital software signing.

- The threat possesses unique characteristics, for example, it is a targeted attack against a government agency using disposable command and control infrastructure and custom malware used only for this one target.

In these cases, you can of course wait until someone else discovers the attack. But as some recent high-profile threat campaigns such as Sunburst have shown, this may be years after the initial breach occurred. Whatever the attackers were originally after, they have long gotten to that point. If you want to avoid that, you need to proactively interrupt the kill-chain, and for that, you must actively hunt for threats.

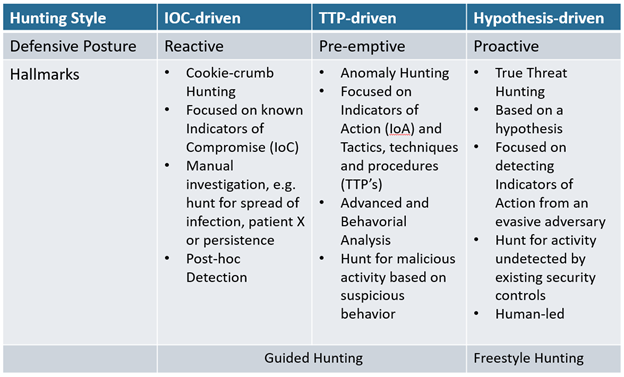

Threat Hunting Styles and Maturity

The table below outlines three different threat hunting styles. You will find that there are similar but slightly different variations of this around. SANS for example published a more verbose but similar categorization that also considers maturity.

Table: Three basic threat hunting styles

You can see that IOC- and TTP-driven threat hunting relies on the successful detection and discovery of at least one IOC, observable TTP, or anomaly. As such, these are primarily used to validate if a breach has occurred and to assess the scope or spread of an intrusion or detection. These deal with the so-called “known-knowns” to use as a cookie crumb to follow. Securonix Autonomous Threat Sweep automates aspects of IOC- and analytics-driven hunting.

Contrast this with hypothesis-driven, or “true” threat hunting, which does not rely on prior detections. Instead, we assume that a threat or threat actor was not detected, but may have successfully targeted and compromised our organization anyway. A hypothesis is defined as “a supposition or proposed explanation made based on limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.”

Having limited evidence is the key here. Threat detection technologies can provide limited evidence — they may discover some of IOCs, but not all of them — and so may subsequently not provide a clear or comprehensive assessment of how advanced or widespread a compromise is.

Even relying on more intelligent and automated technologies such as EDR may be limited by what is visible from the endpoint, requiring that disparate pieces of information are sewn together like a patchwork quilt.

And as we already outlined above, detection technologies may not be able to detect a threat at all if it is a novel or new attack, or has been designed to purposefully evade detection.

Threat Hunting Versus Detection

We need to be very clear — threat hunting is not just a new cool name for searching through logs. Threat hunting is NOT the same as:

- Incident triage

- Incident investigation

- Incident response

One differentiation between detection and hunting could be as follows:

Detection attempts to catch an attack near real-time in the act — hunting is post-hoc and attempts to discover an attack based on a retrospective view of activity.

As we have seen again and again with recent incidents, IOCs may only become known after a threat actor campaign becomes active. In that case, searching for IOCs may also be classed as hunting.

But hunting primarily focuses on threats that existing security controls have failed to detect — so more commonly threat hunting is the search for suspicious activity.

Let us consider an analogy. If you only saw the ripples from a stone thrown into a pond, you would be able to deduce very little. But assess the timing and strength of those ripples from several different points along the pond edge and you will be able to reconstruct when and from where the stone was thrown and even determine how big it was. The impact of a cyberattack is similar, and even a wily attacker leaves some traces that allow us to triangulate their activities.

When to Threat Hunt?

Threat hunting is a labor-intensive exercise, requiring an investment of man-hours with uncertain returns. While the amount of time it takes to conduct a hunting exercise can be reduced through additional technology investments, especially in automation and data collection, storage, and analysis, it cannot be fully automated away. This is because threat hunting is intended to fill the gaps left by technology. If you could detect a threat, you don’t need to hunt for it.

Unless you lack the foundational technologies – threat detection and security event and log collection, storage, and analysis – you should be doing at least some threat hunting, even if this is limited to a manual exploratory analysis after another big cyber event hits the news. So the question is really how much you should be investing in hunting.

How much will depend on three primary criteria:

- Your risk profile

If you expect to be targeted by sophisticated and motivated attackers, especially those with the ability to develop evasive techniques, hunting should be a major part of your security strategy.

- Your available resources

While it’s rare to have more time and people than you need, many security teams do experience calmer periods that can be used for threat hunting. In addition to mitigating gaps in your detection stack, hunting is also useful when engineering new detections or developing new playbooks. It is also a great training tool for novice analysts to gain a deeper understanding of specific threats and to get them quickly familiarized with the business infrastructure and available tools.

If your team is already struggling to stay on top of cyber hygiene and incident response, threat hunting is probably not the right next investment.

- Your current maturity

Threat hunting is not an easy entry-level activity. It requires a thorough understanding of the threat landscape, a high degree of proficiency with security tools, and deep visibility into network, system, and user activity in the form of broad-scope log and event collection. You also ideally need an effective detection architecture and search and analytics tooling, like a SIEM, to hunt.

But even a little bit of threat hunting will address some of the shortcomings of signature and IOC-based detection solutions and will help validate that you haven’t been stealthily compromised.

The data collected for and time spent on threat hunting should be incrementally increased in tandem as your overall security operations maturity grows.

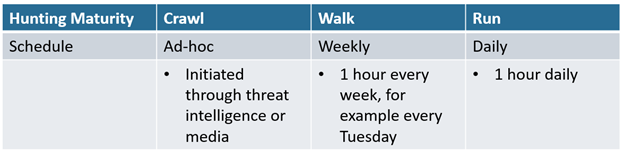

Threat Hunting Maturity

It is possible to take a crawl, walk, run approach to threat hunting by gradually increasing the amount of time spent on conducting hunting exercises.

Measuring ROI for Hunting

Measuring ROI is fraught with ambiguity for a process that may, or may not, yield fruitful results, and that is really where the difficulty lies. The business is usually overjoyed if a business risk is discovered and mitigated early, but it may be difficult to measure the value of a threat hunting program.

Threat hunting falls into the same category as other risk mitigation measures, such as insurance or fire detection and prevention. The value is obvious when there is an incident, but the conclusion of wasted money when nothing happens, or in the case of hunting, nothing is found during the activity, is misleading. Instead, measuring the effectiveness of threat hunting must be tightly coupled with key performance metrics such as the median and mean time to discovery and response (MTTD, MTTR).

What should good tooling for threat hunting include?

There are few dedicated tools for pure threat hunting. Instead, hunters will want the richest data sources available to them, which can vary depending on the environment, budget, and maturity. Searching in raw log files, for example using ‘grep’, is possible and sometimes the last resort, especially for long-term retained data, but suffers from a lack of more sophisticated search and analytics features (especially for visualizations) and terrible performance, especially speed-wise. Log management solutions offer some basic capabilities to search data, but usually don’t include much in terms of analytics. Some organizations may store event data in a database, requiring SQL to search. SQL may offer some powerful means to count, search and operate on data, but as a language does not integrate a security-oriented data model or taxonomy.

A next-generation SIEM like Securonix is the tool of choice for most threat hunters, and it’s easy to see why:

- Data is collected and stored at scale, allowing performant and speedy searching and analysis of event data

- Hunters can leverage natural-language and keyword searching enriched with user, data and asset context, and threat intelligence which truly provides a single pane of glass for investigations as well as deriving insights into threat trends with a user/asset context.

- Hunting can be guided and augmented through security-specific analytics and visualizations including threat models, automation playbooks, and an investigation workbench which allows for a hunter to easily visualize how an attacker or insider is pivoting or progressing through various kill-chain stages.

- Backed up by Securonix Threat Labs, our Threat Hunting team uses our platform and shares their findings and insights, either as Hunting-as-Code or the Autonomous Threat Sweeper service.

Check out why more and more threat hunters are selecting Securonix Next-Gen SIEM as their hunting platform of choice.

Additional Resources

Three Threat Trends: How to Respond for the Pain to Go Away

Automating Cyber Rapid Response and Threat Hunting with Autonomous Threat Sweep

Additional Contributors: Kayzad Vanskuiwalla

[1] It can be argued that Clifford Stoll, the father of digital forensics, was conducting threat hunting when an accounting error for unpaid compute charges led him to start investigating the KGB hackers under Karl Koch.